Apologies for the small type and narrow line spacing. Blogger's fault not mine! If you go to the view menu in your browser bar you can enlarge it and read it more easily.

'The greatest event since the creation of the world, apart from the incarnation and death of him who created it’. Lopez de Gómara to Charles V (1522).

However in his autobiography written in the same year, Charles never mentions the Americas. The Nuremberg Chronicle, published in 1493, does not mention the New World.

The history of the European voyages of exploration may be conveniently divided into two areas.

1. The drive to the east, which was pioneered by the Portuguese

It is generally accepted that Brazil was discovered on April 22, 1500, by Pedro Álvares Cabral, though the expansion westwards across the Atlantic was eventually dominated by the Spanish. Henry the Navigator right), the third son of King João I of Portugal and the English princess, Philippa of Lancaster, gathered round him mapmakers and navigators. He is seen as the father of Portuguese exploration. By 1462 the Portuguese had explored the coast of Africa as far south as Sierra Leone.

In 1486 King João II of Portugal appointed Bartolomeu Dias as the head of an expedition that was to endeavour to sail round the southern end of Africa in the hope of finding a trade route to India.In May 1488 he discovered the Cape of Good Hope, which he originally named the Cape of Storms. The discovery of the passage round Africa proved that the Atlantic and Indian Oceans were not landlocked as had been thought. It enabled Europeans to trade directly with India and other parts of Asia, bypassing the overland route of the Middle East.

In 1497 King João’s successor, Manuel I appointed Vasco da Gama (left) to lead a pioneering voyage to India. On 20 May 1498 the fleet reached Calicut, a centre of the Indian spice trade. This was the first of three voyages to India. Gama died in India in 1524.

2. The drive to the west pioneered by the Spaniards

See here for a review by the distinguished historian, J. H. Elliott of Hugh Thomas' The Golden Age: The Spanish Empire of Charles V.

See here for another (far more critical) review in the Spectator.

Christopher Columbus did NOT sail west to prove the world was round - that was already known. In 1484, he attempted to convince King João II to sponsor a voyage west to the Orient, but Portugal was committed to discovering the sea-route to India via Africa.

See here for another (far more critical) review in the Spectator.

Christopher Columbus did NOT sail west to prove the world was round - that was already known. In 1484, he attempted to convince King João II to sponsor a voyage west to the Orient, but Portugal was committed to discovering the sea-route to India via Africa.

Columbus then turned to Spain in 1486. His first attempt to enlist the support of the Spanish Crown was unsuccessful, but after a lengthy search for support in France and England, Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand finally agreed to sponsor him in 1492.

The voyages east and west differ in that Europe had known of India and China for centuries, whereas the existence of America was totally unsuspected. When Columbus landed in the Bahamas in 1492 America was still viewed as little more than a barrier between Europe and the true prize of the Indies in the East.

By the mid-sixteenth century, however, Spain would control much of the Caribbean, large portions of the Americas and parts of Africa, and have established a foothold in the western Pacific.

Sailing west from the Gulf of Cadiz, Columbus' modest fleet consisted of two small caravels, one square-rigged and the other lateen-rigged, and a 100-ton vessel from Galicia. He was so certain that he was going to arrive in Asia that he carried a letter to present to the Grand Khan and he brought along an Arabic interpreter.

After little over a month at sea, his ships sighted land in what is now known as the Bahamas. The ships sailed on to Cuba and Hispaniola and in January 1493 began the voyage home. When Columbus walked onshore in the Bahamas, he encountered the beginnings of a continent that Europe had no idea existed.The Americas and their people were not supposed to be there. Consequently the Spaniards and later explorers interpreted the peoples and societies of the New World in the light of their existing preconceptions.

After Columbus returned from his first voyage, the rulers of Spain and Portugal realized that their expeditions might lead to territorial disputes. In the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) Pope Alexander VI drew an imaginary demarcation line down what he thought was the middle of the Atlantic. The demarcation line created great confusion as it went through lands that had not yet been discovered. The French, English and Dutch refused to accept it.

Magellan's voyage: In 1518 Carlos I of Spain (the future Charles V) agreed to support an expedition led by the Portuguese captain Ferdinand Magellan to reach the spice islands by sailing west.

His crew of 270 were a mixture of Spaniards, Basques, Italians, Portuguese, Frenchmen, Greeks and an Englishman. He found a way round the southern tip of South America through the Straits that now bear his name, and gave the ocean into which he sailed the name ‘Pacific’ because it seemed less stormy than the Atlantic.

Magellan and his crew were unprepared for the vastness of the Pacific. Their food ran out and the crew boiled their leather bags along with the ships’ rats to eat. They suffered from scurvy, which made their joints grow sore, their gums bleed and their teeth fall out.

On 7 March 1521 his crew reached the small island of Guam, becoming the first Europeans to land on an inhabited island in the Pacific. As he sailed along the northern half of Guam, Magellan found that every enclave contained coconut groves and freshwater springs. Each enclave also held villages with numerous indigenous people, the Chamorros. The islanders were taller than the Spaniards and completely naked. By late afternoon the Spaniards reached (probably) Agana bay. By this time Chamorros were swarming over the ships and carrying away anything loose. The Europeans retaliated by firing crossbows. Magellan named the islands the Islas de los Ladrones (Thieves), a name which remained until they were renamed the Marianas in1668 in honour of the Spanish Queen Regent.

On Saturday morning, 9 March, Magellan’s ships sailed west by southwest and saw no other islands until they reached what were to be called the Philippines. There his crew took part in battles between local groups and Magellan was killed at Mactan in April. Only one of his ships and four of the crew made it back to Spain in September 1522. Its captain Juan Sebastian del Cano, was the first man to circumnavigate the world.

The conquest of Mexico

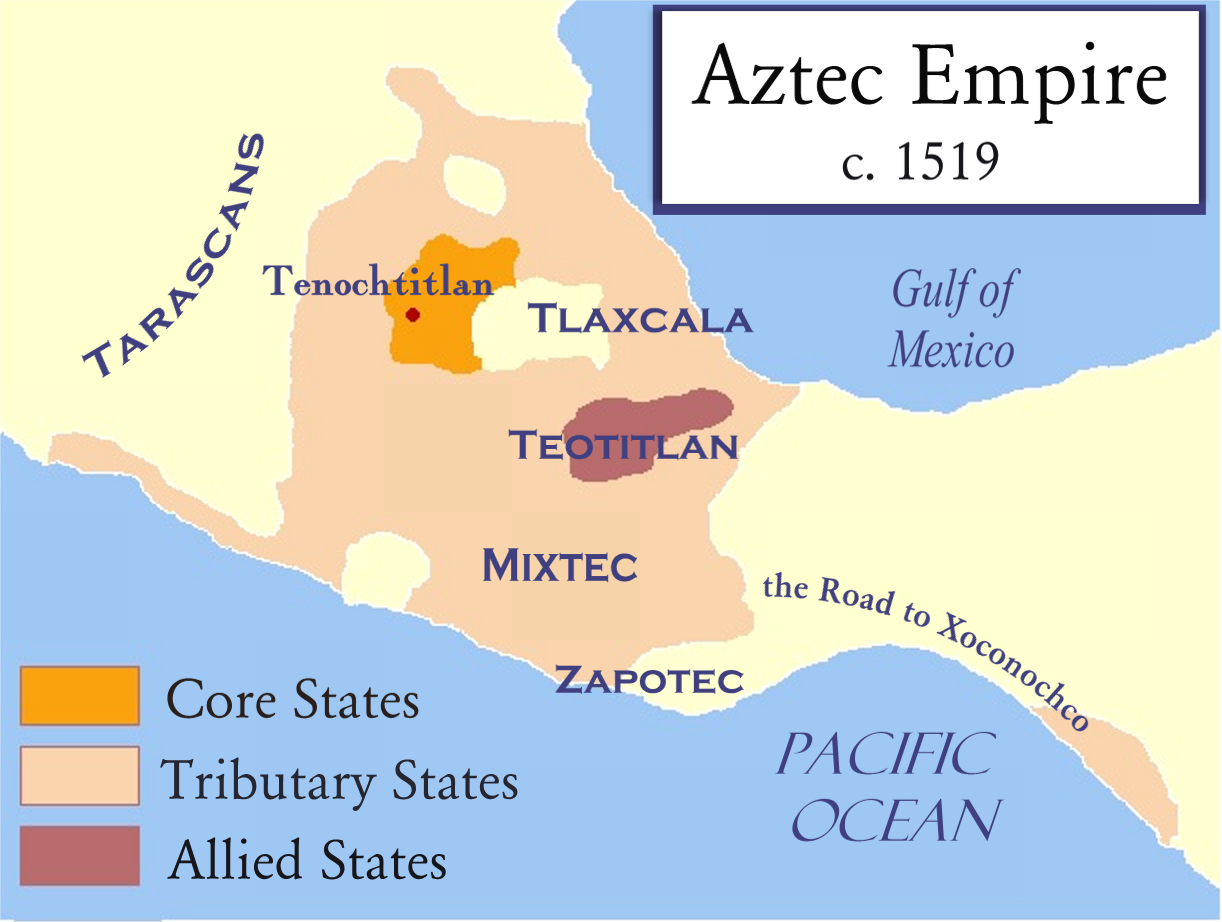

In 1519 Hernán Cortés led an expedition of 600 men and several hundred horses from Cuba to Mexico. By 1521 he had conquered the Aztec (’Mexica’) Empire of c. 25 million people. Moctezuma let Cortés and his followers into Tenochtitlan, but the Spaniards behaved badly and were thrown out. They left behind an invisible enemy in the form of smallpox germs and many people sickened and died. After a long battle Cortés and his Mexica allies captured Tenochtitlan. Moctezuma was imprisoned and probably stoned to death by his own people.

The conquest of Peru

In 1519 Hernán Cortés led an expedition of 600 men and several hundred horses from Cuba to Mexico. By 1521 he had conquered the Aztec (’Mexica’) Empire of c. 25 million people. Moctezuma let Cortés and his followers into Tenochtitlan, but the Spaniards behaved badly and were thrown out. They left behind an invisible enemy in the form of smallpox germs and many people sickened and died. After a long battle Cortés and his Mexica allies captured Tenochtitlan. Moctezuma was imprisoned and probably stoned to death by his own people.

The conquest of Peru

Francisco Pizarro, the illegitimate son of an infantry captain, was the conquistador of Peru and the destroyer of the Inca Empire of 12 million people. This was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. Like the Aztec Empire, it had been built up through conquest. By 1520 it stretched for 3,000 miles along the west coast of South America. Cuzco was the centre of an extensive communications system of roads and bridges, which allowed news to travel about 150 miles a day. Infectious diseases could be carried just as quickly.

In 1532 Pizarro captured Atahualpa (1500?-1533). Though he paid a huge ransom for his release, he was executed. Pizarro founded Lima as Peru’s capital and the Spaniards used this as a base for the exploration and conquest of most of South America.